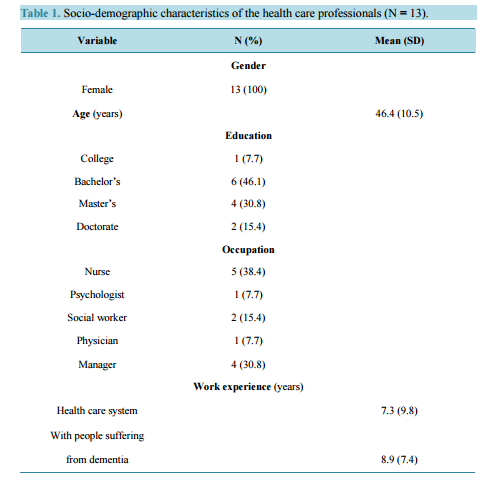

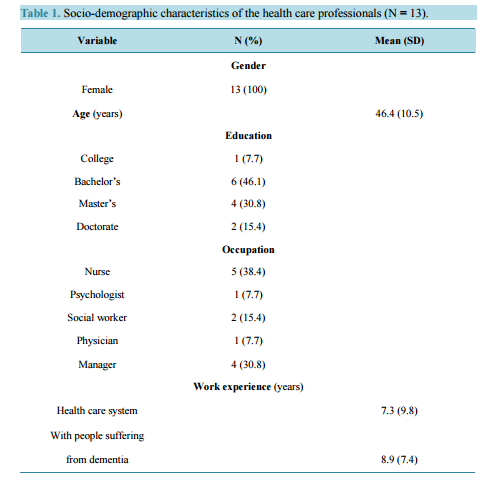

Caring for Inpiduals with Early-Onset Dementia and Their Family Caregivers: The Perspective of Health Care Professionals Francine Ducharme1,2*, Marie-Jeanne Kergoat2,3, Pascal Antoine4, Florence Pasquier5,6, Renée Coulombe2 1 Faculty of Nursing, Université de Montréal, Montréal, Canada 2 Centre de Recherche, Institut Universitaire de Gériatrie de Montréal, Montréal, Canada 3 Memory Clinic, Institut Universitaire de Gériatrie de Montréal, Montréal, Canada 4 Unité de Recherche en Sciences Cognitives et Affectives (URECA), Maison Européenne des Sciences de l’Homme et de la Société (MESHS), Université Lille 3 Charles de Gaulle, Lille, France 5 Centre National de Référence pour les Patients Jeunes Atteints de la Maladie d’Alzheimer et Maladies Apparentées, Lille, France 6 Université Lille Nord de France, Lille, France Email: * [email protected] Received 23 September 2013; revised 17 November 2013; accepted 27 November 2013 Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract The phenomenon of early-onset dementia remains an under-researched subject from the perspective of health care professionals. The aim of this qualitative study was to document the experiences and service needs of patients and their family caregivers for optimal clinical management of early-onset dementia from the perspective of health care professionals. A sample of 13 health care professionals from various disciplines, who worked with inpiduals who suffered from Alzheimer’s disease or related disorders and their family caregivers, took part in focus groups or semi-structured inpidual interviews, based on a life course perspective. Three recurrent themes emerged from the data collected from health care professionals and are related to: 1) identification with the difficult experiences of caregivers and powerlessness in view of the lack of services; 2) gaps in the care and services offered, including the lack of clinical tools to ensure that patients under age 65 were diagnosed and received follow-up care, and 3) solutions for care and services that were tailored to the needs of the caregiver-patient dyads and health care professionals, the most important being that the residual abilities of younger patients be taken into account, that flexible forms of respite be offered to family caregivers and that training be provided to health care professionals. The results of this study provided some innovative guidelines for optimal clinical management of early-onset dementia in terms of the caregiver-patient dyad. * Corresponding author. F. Ducharme et al. 34 Keywords Early-Onset Dementia; Family Caregivers; Perspective of Health Care Professionals; Service Needs 1. Introduction Advances in the development of diagnostic tools have resulted in more cases of dementia being identified in younger people. Considered by the American Alzheimer’s Association [1] to be a national challenge, early-onset dementia is raising questions about the quality of life of the family system affected by the illness at a younger age. Distinctions can be made between younger persons and older persons suffering from dementia. The most important differences between early- and late-onset forms of the disease are: a broader spectrum of clinical profiles (Alzheimer’s disease, frontotemporal lobe degeneration, focal atrophy, subcortical vascular dementia and Lewy body dementia); pervasiveness of certain cognitive symptoms; severity of neuropsychiatric signs and changes in character and behaviour [2]. The experiences of family caregivers of early-onset dementia patients have been explored and described in several qualitative studies over the last decade [3]-[6]. These studies show that family caregivers of inpiduals suffering from early-onset dementia are often their spouse, in their 50 s, who still have children at home and are also looking after an elderly parent suffering from gradual loss of autonomy [7]. Their life partner’s illness has multiple repercussions on the socio-professional, financial and psychological aspects of family life and studies show that the burden of these caregivers is even greater than that of caregivers of elderly inpiduals with the same illnesses [8]-[10]. Specific factors undermining quality of life of the caregiver-patient dyad identified in a previous study include: problems managing the behavioural and psychological symptoms associated with the illness, which are often more significant at a younger age; a longer quest for diagnosis, as the signs and symptoms observed are often attributed to other conditions; non-disclosure to others and denial of diagnosis, as the illness is mainly associated with old age and younger people who have it are marginalized; grief for loss of midlife projects, difficulty assuming an unexpected role and planning for the future [4]. In spite of this knowledge about the experiences of patients and family caregivers, the phenomenon of earlyonset dementia remains an under-researched subject from the perspective of health care providers. Specifically, the experience of health care providers in caring for persons with early-onset dementia and their caregivers is unknown, as is their perception of optimal clinical management for this emergent population in the health care system. As pointed out over a decade ago, recommendations on dementia services for younger people and their families are not based on scientific evidence [11] and research is needed to gain a more in-depth understanding of the experience of these professionals so services tailored to the needs of patients and their caregivers can be developed. The services used by families of older patients are still not geared toward younger patients and their caregivers, and what is being decried is the lack of programs developed specifically for younger patients and their families [12] [13]. Against this backdrop, we undertook a project to document the experiences of patients and family caregivers and their service needs for optimal clinical management of early-onset dementia from the perspective of health care professionals. 2. Methods 2.1. Design In view of the lack of empirical research on the subject, a qualitative design was selected to explore the perceptions of health care professionals. 2.2. Setting, Sample and Recruitment Health care professionals were recruited from memory clinics associated with a centre of excellence in cognitive health of an integrated university network, including hospitals and local community health and social services centres in a large metropolitan centre in Quebec (Canada). Neurologists, psychiatrists and geriatricians at these F. Ducharme et al. 35 clinics regularly diagnose dementia. Other participants were recruited from Alzheimer societies that provide support to young patients and their family caregivers. Participants had to meet the following selection criteria: be a health care professional with a minimum of one year’s experience working with patients age 65 or under who suffer from Alzheimer’s disease or related disorder and their family caregivers. The health care professionals were approached by the project coordinator to assess their interest in participating in focus groups to share their perceptions of the experiences of patients and their family caregivers, and to give suggestions on what services could help optimize the provision of care. A focus group was formed once 4 to 6 participants were interested. The number of groups was determined by data saturation or redundancy emerging from the participants’ discourse [14] [15]. Two focus groups were thereby formed consisting of 5 and 6 participants respectively (n = 11). As two health care professionals who had pertinent expertise were not available to participate in either of the two groups, the study coordinator conducted two inpidual interviews using the same interview guide, thereby bringing the total number of participating health care professionals to 13. These professionals (all women) had different disciplinary backgrounds: nursing, psychology, social work, medicine. Some perform coordination or advisory functions (case managers) at memory clinics or Alzheimer societies. The participants had a mean age of 46.4 years (S.D. = 10.5), had several years’ experience in the health care system (X = 17.3, S.D. = 9.8), specifically 8.9 years’ (S.D. = 7.5) experience working with dementia patients, including perse experience with young people. Specifically, all the health care professionals who participated worked occasionally (82%), fairly often (23%) or often (15%) with this population in their recent years of practice. The vast majority were university educated (92%) (see Table 1 for the key characteristics of the participants). Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of the health care professionals (N = 13). Variable N (%) Mean (SD) Gender Female 13 (100) Age (years) 46.4 (10.5) Education College 1 (7.7) Bachelor’s 6 (46.1) Master’s 4 (30.8) Doctorate 2 (15.4) Occupation Nurse 5 (38.4) Psychologist 1 (7.7) Social worker 2 (15.4) Physician 1 (7.7) Manager 4 (30.8) Work experience (years) Health care system 7.3 (9.8) With people suffering from dementia 8.9 (7.4) F. Ducharme et al. 36 2.3. Data Collection Tool A group interview guide was designed taking into account the care trajectory of patients and their family caregivers, namely with reference to the current and potential offer of services to support them. Like RosenthalGelman and Greer [16], we drew inspiration from pertinent conceptual frameworks in designing the interview guide, namely a life course perspective [17] and a family systems approach [18]. The life course perspective emphasizes the importance of the timing of the events affecting the inpiduals and their families. Receiving a diagnosis of early-onset Alzheimer’s disease or related disorder is a non-normative event and gives rise to particular needs and unforeseen difficulties in life trajectory. With a family systems approach, the focus is on the interaction and interdependence among family members and emphasizes that any change, such as a health problem, in one of its members will have repercussions on all the others. This approach involves not only considering the person suffering from early-onset dementia but also his primary family caregiver and family network. The guide included open-ended questions pided into four main sections. The first covered the health care professionals’ overall experience with early-onset dementia (e.g., Please indicate how you are involved in the care of early-onset dementia patients and their caregivers in your workplace?). The second section dealt with the care trajectory of patients and their families (e.g., How does it work when you have to help and support a young person diagnosed with dementia and his/her caregivers in the care trajectory?). The expected responses pertained to the professionals perceptions regarding early-onset dementia and the problems encountered by patients, family caregivers and the family network, and those encountered by themselves as members of the formal support system for patients and their families. In order to further operationalize the comments collected from participants, the third section asked each professional to present two opposite cases, namely a complex case where they felt that a follow-up went well, and another where it didn’t based on their inpidual assessment (Can you each tell me about at least one complex case where you felt that the follow-up was satisfactory? And another complex case where it wasn’t?). The aim of the exercise was to specifically identify the resources and means used to support patients and their families, among others, their primary family caregiver. In this last part of the discussion, participants were asked to imagine the ideal situation for addressing the problems identified, namely how the services could be evolved so that the unique needs and problems of these patients and their families be better taken into account for the purposes of optimal clinical management (Regarding the case follow-up problems you identified, what changes could be made so that the needs and resources be better taken into account young patients and their families be better supported?). This part of the discussion allowed us to identify innovative solutions and proposals to evolve the care and support practices. The session ended with a sociodemographic questionnaire that participants answered on their own. On average, the group discussions lasted for 120 minutes, including an initial period for signing the consent form to participate in the study and a final period for collecting the socio-demographic and descriptive information. 2.4. Data Collection Procedure The project was approved by the ethics review boards of the recruitment sites (CER IUGM 10-11-018). The study coordinator contacted professionals from the memory clinics associated with the centre of excellence for cognitive health and Alzheimer societies by telephone to explain the purpose of the study, verify the inclusion criteria and ask if they were interested in participating in a focus group, outside of work hours, at a location close to their workplace. A lump sum to cover their transportation and parking expenses was offered. The focus groups were held in a central location, in a comfortable room in one of the facilities associated with the centre of excellence. The date of the focus group was determined at the convenience of the participants and the interview guide was sent by email one week prior to the session to allow participants to reflect on the various topics and clinical situations of their case load. On the day of the focus group, the participants signed the consent form on arrival. The discussion was led by a trained group facilitator along with an observer who ensured the proper conduct of the session, namely that all the topics were covered and that each participant had the chance to speak. This person also ensured the quality of the audio recording of the group sessions and took notes on the non-verbal behaviour of the participants or made other observations related to the climate of the interview [19]. F. Ducharme et al. 37 2.5. Data Analysis The data from the recordings of the group discussions were fully transcribed in electronic format and analyzed by group [19], and were then combined with the recordings of the qualitative data from the two additional inpidual interviews. Content analysis was performed using QDA Miner, version 4.0, a qualitative data analysis software. The analysis consisted of coding the transcripts using the Huberman and Miles approach [15], namely identifying the units of meaning to which a code was assigned. After having read the transcript of the first discussion group, two members of the team developed an initial coding scheme by noting the statements deemed to be significant in relation to the purpose of the study and the various topics covered. Inter subjective verification was performed and consensuses were established in this first round of coding, which were then used to analyze the thematic content of subsequent data, namely the second discussion group and the two inpidual interviews. The recurring themes from the transcripts and the communalities of the participants comments (convergence of discourse) were sought. The analysis was also used to index the opposite clinical cases, namely those regarding the successes and failures of case follow-ups. 3. Results The recurring themes from the comments collected from the health care professionals pertain to three main aspects, namely: 1) identification with the difficult experiences of caregivers and powerlessness in view of the lack of services; 2) gaps in the care and services offered and 3) solutions for care and services that are better tailored to the needs of the caregiver-patient dyads and health care professionals. The results are presented based on these themes and are illustrated by excerpts from the transcripts. 3.1. Identification with the Difficult Experiences of Caregivers and Powerlessness in View of the Lack of Services All the health care professionals pointed out the problem they had in dealing with the caregivers’ difficult experiences, a problem that seems to be linked to identifying with these people who were often in their same age group. The issue of working with these young family caregivers, the fact that they are marginalized and are often in a situation of being double caregivers, namely caring for their spouse and for an elderly relative, are aspects that particularly affected the professionals, who seem to project themselves into the world of these caregivers, and one that is in the realm of possibility at their age: … it’s like sitting in front of a mirror with the thought that it could be me… it affects me particularly in view of their age, because it’s their spouse who is 52 - 53 years old and the caregiver is still working…. The reality is that she has to keep working, just like us. It’s difficult to give them the support they need (Participant 08/FG2, p.3-4). … People age 48, 53, 58 are coming to see me and they’re my age, and like me, their parents are still around!…. (Participant 07/FG2, p.3). The health care professionals also feel extremely powerless in view of the lack of services and support programs tailored to the needs of these patients. Where do we refer these people who are suffering from cognitive impairment at a young age? What services can we offer these patients and their families? The health care professionals interviewed indicated that they felt extremely helpless in view of this situation, as eloquently expressed in many of the excerpts from the transcripts: “No case file is opened and there are waiting lists everywhere… I really feel powerless… and I get calls from nurses from the clinics who say: we’d like to do something, but what can we offer them while waiting for the diagnosis?… there’s something missing in the system… but what? (Participant 04/FG1/p.41). … I’m often troubled. I feel like thre’s a “box” missing for these young people… to refer them to the right place… it doubles the stigma of an illness that already has one attached.… there’s nothing we can do… (Participant 10/FG2/p.5, 35). In their comments, the health care professionals constantly indicated having problems managing this population as there were important gaps in the care and services offered in the current context. 3.2. Gaps in the Care and Services There was a consensus on the scarcity or complete lack of facilities and clinical tools to provide care to those under age 65, both for a diagnosis and follow-up: F. Ducharme et al. 38 … no care is generally provided in memory clinics to those under age 65… (Participant 01/FG1/p.46). There aren’t a lot of resources. I think about the people I"ve had to turn away… I can’t help them. When I call and tell them they have to be age 65 to get services, they understand, but they then ask me, so where do we go? (Participant 02/FG1/p.44). … we have some great screening tools for our elderly patients, but would my colleagues know how to screen young people who turn up at the hospital with problems like this? They’re beautiful and young, and you can’t tell by looking at them (Participant 04/FG1/p.24). We know that frontotemporal dementia often occurs at a younger age with all the behaviour disorders… these are needs that require specific services, especially if their behaviour is affected… and we don"t have the skills or resources (Participant 02/FG1/p.33). Specifically, the health care professionals noted a lack of coordination in the services offered to young people and their families and a need for psychosocial support: We have a “silo mentality” when it comes to what is being offered to people. We have to start thinking outside the box (Participant 11/FG2/p.6). The social workers at the community centre don’t have the time to provide psychosocial support. They’re increasingly becoming administrators and service managers of home support services… and don’t have any time to provide psychosocial support… (Participant 13/inpidual interview). Faced with their powerlessness and the gaps in the care and services that they identified, the health care professionals indicated what needs to be changed and proposed some innovative solutions regarding the preferred services model to meet the needs of the caregiver-patient dyads and those of health care professionals. 3.3. Solutions for Care and Services Tailored to the Needs of the Caregiver-Patient Dyads and Health Care Professionals The solutions proposed by the health care professionals relate to patients and their family caregivers, as well as their own problems dealing with this population. In terms of the patients, the early detection of the illness and a more persified and flexible offer of services to ensure quality of follow-up were proposed. From a systemic perspective, this offer of services should not only take into account the respect of the patients’ residual abilities, but also the unique needs of their caregivers, particularly their need for respite. 3.3.1. Detection of the Disease and More Diversified and Flexible Offer of Services For health care professionals, earlier detection of the disease in young people is a priority concern that needs to be addressed: How do we detect this, something’s missing in the system… there could be screening, people could be prioritized to get access to this screening and they could more readily referred to the right resources (Participant 04/FG1/p.41). In the resources indicated, the health care professionals mentioned the need to develop new persified and more flexible services for the caregiver-patient dyads, including psychosocial services at home and to have a phone line and services that use information and communication technologies taking into account the age of the dyads: … equip them psychologically so they’re more confident in their daily lives and with their own resources at home (Participant 08/FG2/p.57). When the illness evolves… have a hotline for family caregivers… a place that is accessible, for example, at the Alzheimer society (Participant 04/FG1/p.72) In the future, perhaps organize a forum of some kind, like online training… that would give everyone access and where people could get answers to their questions at any time (Participant 03/FG1/p.76). For health care professionals, respite is a priority need for caregivers, which also requires more flexible, creative and different solutions than those usually offered. The health care professionals spoke of “tailored respite” that would allow caregivers to stay in the workforce and let them have more time for their personal and family activities with children or teenagers who are often still living at home and other family members: … more creative ideas… perhaps going into a centre is not really for them (young people)… maybe have someone at home with them doing an activity they enjoy while the caregiver goes to work (Participant 09/FG2/ p.60). F. Ducharme et al. 39 For caregivers, it would be great if they could be given a respite passport… (Participant 01/FG1/p.13). That respite be given right from the start… as a package. As soon as the diagnosis is made, this could be a first approach… they would be given a coupon entitling them to a weekend or a week at a given date… caregivers wouldn’t thereby feel like they’re asking for the service (Participant 03/FG1/p.79). Or, we could set up a respite model that allows a spouse to get away for a weekend with the kids to an outdoor activity centre and someone could look after the patient at home… (Participant 04/FG1/p.79). Taking into account the physical and residual cognitive abilities of patients, among others things, their ability to work and the development of systemic family interventions were also part of the recurring innovative solutions proposed by the health care professionals. 3.3.2. Taking into Account Young Patients’ Residual Abilities The health care professionals indicated the importance of developing activities tailored to the residual potential of these young patients: Give lots of information, especially on the abilities… cognitive stimulation… physical exercise… fun activities (Participant 01/FG1/p.69). … set up different groups for younger patients and older patients, because the needs are different (Participant 09/FG2/p.39). In view of the evolution of the illness, the importance of having a smooth transition in the services offered to patients was indicated. For example, young people could take part in support groups specifically designed for them in the early stages of the illness, and then volunteer at recreation centres for seniors where they could offer their expertise and skills and, finally, they could take part in the activities organized at these same centres once their loss of autonomy becomes more severe: The illness evolves, so they’re no longer able to attend this type of group (group for people in the early stages of the illness)… they could be taken to a recreation centre that is mainly for seniors… where they recently volunteered… and then they feel really valued … and slowly get into the centre… this is a model that could also be used in day centres (Participant 05/FG1/p. 63). For the health care professionals, preserving the young people’s ability to work is essential for maintaining their self-esteem and sense of being useful: … young people want to stay physically active… they need to exert themselves physically and there’s nothing better than doing something productive, therefore having a job that’s adapted to young people suffering from dementia because they want to feel useful, even if it involves doing a repetitive task (Participant 07/FG2/p.15). … depending on the type of work they used to do, I feel they can still work. But often, they stop working when the diagnosis is made, it"s devastating, so they stop doing everything… we can find them something suitable to do at the onset of the illness, it helps them to keep going… (Participant 03/FG1/p.30). Lastly, the health care professionals acknowledge the importance of using a more systemic approach to the care and services, namely to not consider the patient and the illness in isolation, but rather as part of a family system. 3.3.3. A more Systemic Approach to the Care and Services Taking into Account the Family A systemic approach where the family is taken more into consideration is favoured by the health care professionals: … thinking of the caregivers for whom things are really difficult, for example, when the behaviour of those suffering from frontotemporal dementia changes drastically. It’s really hard for the caregivers… thinking about the caregivers and the whole family in the intervention, in terms of psychosocial support, and not just about the patient (Participant 02/FG1/p.70). The kids… meeting with them also helps them to deal with things (Participant 01/FG1/p.61). In terms of the necessity of this more systemic approach that takes into account the family as a whole, the participants specifically mentioned that not only the patients should be considered as clients of the health care system, but so should their primary family caregivers, in view of their high needs and the impact of their role on their own health. The possibility of opening a file in the name of the caregiver was mentioned so their own need for care and services is recognized: A file could be open for family caregivers, as they might also require services (Participant 04/FG1/p.15). Solutions were proposed regarding the needs of the health care professionals who work every day with patients and their families. In view of their powerlessness, the health care professionals confess their lack of training to F. Ducharme et al. 40 intervene with this specific population and the need to acquire knowledge to help them improve their feeling of competence and control. 3.3.4. Training that Takes into Account the Particular Characteristics of the Young People and Their Family Caregivers All the participants pointed out the need for better training so they can have innovative intervention strategies for young patients and their families, strategies that are different from those used with older people. To accomplish this, the expertise of mental health specialists was mentioned many times as being a precious resource that could be used more and taken advantage of: … we need training… mental health workers could let us know some of their approaches… (Participant 07/FG2/p.61). As we have very little to offer in terms of medication, the idea is to support people in relation to their symptoms… we need to learn what to do. We should combine the skills of health care professionals with those of mental health workers to deal with situations like these (Participant 11/FG2/p.38). Training in medical clinics… I get calls from doctors and hear comments… but most of the comments I get is that they don’t feel well equipped: we need staff who have better mental health training… they are mainly trained for physical care… and dementia isn’t covered in the training (Participant 08/FG2/p.38). In short, the health care professionals are sensitive to the unique experiences of the dyads who are living with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease or related disorders, experiences with which they seem to identify. Faced with their feeling of powerlessness due to the lack of resources, they point out the importance of developing services geared toward the specific needs of the dyads. In this regard, many proposals based on their experience were made to promote quality care practices and improve their expertise, which they feel is lacking with this specific population. In the next section, we will discuss these results. 4. Discussion The perceptions of the health care professionals regarding the experiences and preoccupations of family caregivers of people suffering from early-onset dementia are consistent with those mentioned by the family caregivers themselves and documented in the literature [4] [20]. These professionals also told us about specific elements of their own experience that need to be taken into account in the training they are asking for, so as to better intervene with this specific population. In particular, their identification with and projection they made relating to the lived experience of the caregivers and their feeling of powerlessness should not be overlooked. The health care professionals are often the same age as the family caregivers they meet and thereby identify with the difficult situation and suffering they are going through on a daily basis. From this perspective, the training of these professionals should not just include aspects surrounding the distinctive signs and symptoms of early-onset dementia. As the stigma associated with the disease influences perception, more predominantly at a younger age [21], the training should also include the perceptions the professionals have of the illness, and any associated myths and taboos. Discussing uncertainties, values and beliefs about the illness, as well as having the opportunity to share clinical stories with patients and their families is part of a narrative pedagogy that might help reduce the phenomenon of identification and increase the sense of control of practitioners [22]. As for the learned powerlessness from having contact with inpiduals who suffer from early-onset dementia and their family caregivers and relating to the lack of resources, it could very likely be limited or reduced if the suggestions from the health care professionals, based on their experience and expertise, were taken into account by managers in developing care and services in line with the specific needs of this population. Like patients and families, health care professionals are important stakeholders in the design of tailored interventions. This approach could help not only reduce the feeling of helplessness but also empower the health care professionals [23]. Among other things, the interest in exploring existing interventions in the field of mental health and referring to the expertise of mental health professionals, as mentioned by the participants, is particularly interesting. The data collected in this study underscore the importance of having faster access to screening and diagnosis in terms of the care and services to offer the caregiver-patient dyads. The long quest for diagnosis has often been mentioned in studies on family caregivers of young patients to be a source of suffering [4] [24]. The relationships between family physicians and second-line specialists need to be tightened so that faster screening is possible. However, it is not just faster access to diagnosis that is important for the quality of life of patients and F. Ducharme et al. 41 their family members, but also that required services be offered as soon as the diagnosis is made and that the uncertainty and powerlessness [25] for both professionals and the caregiver-patient dyads be reduced. In this perspective, better coordination between memory clinics and the various community organizations is required. As mentioned above, being diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s or related disorder is, based on a life course perspective, a non-normative event that gives rise to particular needs and unforeseen difficulties in life trajectory. In this context, our study clearly underscores the need for specific measures of support further to the diagnosis. This is why the health care professionals noted other elements to be considered in the services to offer this particular population. The fact that the majority of these younger people are still active and generally have fewer chronic health problems is one of these specific elements, which means that different activities than those offered to seniors are needed. The day centres, as currently designed, do not meet the needs of these more active young patients who often have just left the workforce and still have residual skills that could be put to use. As suggested in the literature [11], some of the support interventions required by family caregivers of persons with dementia are generic. These include support at time of diagnostic disclosure, help managing changes, learning to assume the caregiver role, and juggling other responsibilities [26]-[28]. From the perspective of the health care professionals, the results of our study underscore that other more specific support measures are needed for caregivers of patients with early-onset dementia. More persified forms of care and support, offered in various forms (psychosocial intervention at home, telephone or online intervention) were proposed to meet the varied needs of these younger patients and avoid the “one-size-fits-all” formula that, according to the studies, only has modest effects on the quality of life of caregivers [26]. The considerable need for respite that requires the development of innovative forms to take into account caregivers in the workforce and children, who often are still living at home, was also mentioned. By recognizing several specific needs of caregivers, health care professionals thereby propose that caregivers are considered as clients of the services and, as such, that a clinical file is opened for them. In a broader sense, in light of the numerous losses experienced by the young patients, their family caregivers and their entire families, the health care professionals suggest that a care and service model that uses a more systemic approach, namely one that takes into account the family system, is developed. This care and services model is certainly relevant in the current context but needs a paradigm shift towards a family-centered approach. An expert case manager or, as suggested by Beattie and his colleagues, an expert in dementia care [11], could be assigned to the family following diagnostic disclosure in order to assess specific support needs collaboratively. Such an approach will have to be offered using a realistic and feasible approach to avoid overburdening the caregiver-care receiver dyads. Lastly, the results of this study and its underlying theoretical perspectives, namely the life course perspective [17] and family systems theory [18], offer some innovative guidelines for developing professional interventions for optimal clinical management of early-onset dementia, guidelines that take into account not only the patients and their illness, but also the caregiver-patient dyad, and the impact of the illness on the entire family system. It is important to note that, in spite of its small size, data saturation was achieved with the sample of this study. Obviously, other studies conducted in various contexts will ensure the transferability of these initial findings that provide knowledge about a recent care and service problem, namely with the advent of tools to identify the disease earlier and earlier. Acknowledgements Project funded by the Fonds de recherche du Québec-Santé (FRQS), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Canada) and the Agence nationale de recherche (France). References [1] Alzheimer’s Association (2013) Early Onset Dementia: A National Challenge, a Future Crisis. http://www.alz.org/national/documents/report_earlyonset_full.pdf [2] Mendez, M. (2006) The Accurate Diagnosis of Early-Onset Dementia. International Journal of Psychiatric Medicine, 36, 401-412. http://dx.doi.org/10.2190/Q6J4-R143-P630-KW41 [3] Bakker, C., de Vugt, M., Vernooil-Dassen, M., van Vliet, D., Verhey, F. and Koopmans, R. (2010) Needs in Early onset Dementia: A Qualitative Case from the NeedYD Study. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, 25, 634-640. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1533317510385811 F. Ducharme et al. 42 [4] Ducharme, F., Kergoat, M.-J., Antoine, P., Pasquier, F. and Coulombe, R. (2013) The Unique Experience of Spouse in Early-Onset Dementia. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, 28, 634-641. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1533317513494443 [5] Lockeridge, S. and Simpson, J. (2012) The Experience of Caring for a Partner with Young Onset Dementia: How Younger Carers Cope. Dementia, 12, 635-651. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1471301212440873 [6] Roach, P., Keady, J., Bee, P. and Hope, K. (2008) Subjective Experiences of Younger People with Dementia and Their Families: Implications for UK Research, Policy and Practice. Review in Clinical Gerontology, 18, 165-174. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0959259809002779 [7] Williams, T., Dearden, A. and Cameron, I. (2005) From Pillar to Post: A Study of Younger People with Dementia. Psychiatric Bulletin, 25, 384-387. http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/pb.25.10.384 [8] Arai, A., Matsumoto, T., Ikeda, M. and Arai, Y. (2007) Do Family Caregivers Perceive More Difficulty When They Look after Patients with Early Onset Dementia Compared to Those with Late Onset Dementia? International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 22, 1255-1261. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/gps.1935 [9] Freyne, A., Kidd, N., Coen, R, and Lawlor, B. (1999) Burden in Carers of Dementia Patients. Higher levels in carers of younger sufferers. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 14, 784-788. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1166(199909)14:9<784::AID-GPS16>3.0.CO;2-2 [10] Kaiser, S., and Panegyres, P. (2007) The Psychosocial Impact of Young Onset Dementia on Spouses. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, 21,398-402. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1533317506293259 [11] Beattie, A., Daker-White, G., Gilliard, J. and Means, R. (2002) Younger People in Dementia Care: A Review of Service Needs, Service Provision and Models of Good Practice. Aging and Mental Health, 6, 205-212. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13607860220142396 [12] Chaston, D., Polland, N. and Jubb, D. (2004) Young Onset Dementia: A Case For Real Empowerment. Journal of Dementia Care, 12, 24-26. [13] Coombes, E., Colligan, J. and Keenan, H. (2004) Evaluation of an Early Onset Dementia Service. Journal of Dementia Care, 12, 35. [14] Denzin, N. and Lincoln, Y. (2003) Handbook of Qualitative Research. Sage, Toronto. [15] Miles, M. and Huberman, A. (2003) Qualitative Data Analyses. Sage, Toronto. [16] Rosenthal Gelman, C. and Greer, C. (2012) Young Children in Early-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease Families: Research Gaps and Emerging Services. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, 26, 29-35. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1533317510391241 [17] Bengtson, V. and Allen, K. (1993) The Life Course Perspective Applied to Families Over Time. In: Boss, P., Doherty, W., LaRossa, R., Schumm, W. and Tenmetz, S., Eds., Sourcebook of Family Theories and Methods, Plenum, New York, 469-504. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-85764-0_19 [18] Whitchurch, G. and Constantine, L. (1993) Systems Theory. In: Boss, P., Doherty, W., LaRossa, R., Schumm, W. and Tenmetz, S. Eds., Sourcebook of Family Theories and Methods, Plenum, New York, 325-352. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-85764-0_14 [19] Wilkinson, S. (2003) Focus Groups. In: Smith, J. Ed., Qualitative Psychology, Sage, Toronto, 184-204. [20] Van Vliet D., de Vugt, M., Bakker, C., Koopmans, R. and Verhey, F. (2010) Impact of Early Onset Dementia on Caregivers: A Review. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 25, 1091-1100. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/gps.2439 [21] Phillips, J., Pond, C.D., Paterson, N.E., et al. (2012) Difficulties in Disclosing the Diagnosis of Dementia: A Qualitative Study in General Practice. British Journal of General Practice, 62, 546-555. http://dx.doi.org/10.3399/bjgp12X653598 [22] Diekelman, N. (2001) Narrative Pedagogy: Heideggerian Hermeneutical Analyses of Lived Experiences of Students, Teachers and Clinicians. Advances in Nursing Science, 23, 53-71. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00012272-200103000-00006 [23] Lévesque, L., Ducharme, F., Hanson, E., Magnusson, L., Nolan, J. and Nolan, J. (2010) A Qualitative Study of a Partnership Approach to Service Needs with Family Caregivers on an Aging Relative Living at Home: How and Why? International Journal of Nursing Studies, 47, 876-887. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.12.006 [24] Harris, P. and Keady, J. (2004) Living with Early Onset Dementia. Alzheimer’s Care Quarterly, 5, 111-122. [25] Mishel, M. (1988) Uncertainty in Illness. Image, 20, 225-232. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.1988.tb00082.x [26] Lopez-Hartmann, M., Wens, J., Verhoeven, V. and Remmen, R. (2012) The Effect of Caregiver Support Interventions for Informal Caregivers of Community-Dwelling Frail Elderly: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Integrated Care, 12. Published on Line August 10, 2012. http://www.ijic.org F. Ducharme et al. 43 [27] Scotland’s National Dementia Strategy (2013) Five Pillars Model of Post-Diagnostic Support. http://www.alzscot.org/campaigning/national_dementia_strategy [28] Prorok, J., Horgan, S., and Seitz, D. (2013) Health Care Experiences of People with Dementia and Their Caregivers: A Meta-Ethnographic Analysis of Qualitative Studies. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 185, E669-E680.